Overview

This toolkit was created by the BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence on Dementia Caregiving (PHCOE-DC). Funded by the CDC as part of the BOLD Act, PHCOE-DC aims to assist state, tribal, and local public health agencies in developing their dementia caregiving-focused programming and initiatives.

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide potential strategies and interventions that public health agencies can implement to support and elevate the work of family dementia caregivers in their jurisdictions, that are consistent with the Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map. This toolkit may be useful for all public health agencies as they set and pursue their dementia caregiving goals, but especially to public health departments that were awarded funding through the BOLD Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act as they implement their Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) strategies using the Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map as a guide.

Public health agencies may use this toolkit as a source of ideas and inspiration when deciding what strategies and actions to undertake but should not interpret them as recommendations. Agencies should first seek to understand the unique resources and needs of dementia caregivers in their jurisdiction, and then either select or adapt any of the strategies in this toolkit or develop new approaches that better fit their community. Also, this manual is not a compendium of all possible public health approaches, and there may be additional actions public health agencies can take that are not presented here. And, while other ADRD dementia strategic plans exist, this toolkit is limited to state and county examples.

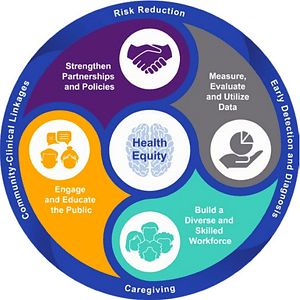

In alignment with the HBI State and Local Road Map for Public Health, 2023-2027, the strategies and examples highlighted in this toolkit are organized into the four domains of public health action that are core to the framework of the Road Map: Strengthen Partnerships and Policies; Measure, Evaluate, and Utilize Data; Build a Diverse and Skilled Workforce; and Engage and Educate the Public.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE HEALTHY BRAIN INITIATIVE ROAD MAP

The four domains of the HBI Road Map framework are built from the Essential Public Health Services. The framework is centered on the principles of health equity and surrounded by the areas of practice across the life course.

The Strategies from State Dementia Strategic Plans section illustrates different types of dementia caregiving strategies public health agencies have selected over the years. These strategies were extracted from previously published state dementia strategic plans and are not attributed to individual states.

The State Implementation Examples section showcases how some states and counties decided to implement caregiving-related goals included in their strategic dementia plans.

Finally, caregiver quotes embedded through out the document are from members of the PHCOE-DC Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG, pronounced “league”) and highlight their lived experiences. Their words illustrate why public health action is needed, and the impact it can have on caregivers’ lives. LEAG members granted permission for their names to be listed in this document.

Notes about terminology

- The terms family caregivers, care partners, and informal caregivers are used interchangeably throughout this toolkit to refer to non-professional caregivers, that is, relatives and friends who provide care and support to a person living with dementia.

- Dementia caregiving strategies refers to a variety of activities, programs, and initiatives public health agencies can implement to support family caregivers.

Introduction to Dementia Caregiving

Who are dementia caregivers and what do they do?

Dementia caregivers are family members, friends, and other members of the community who provide care to people living with dementia. They are also referred to as unpaid, family caregivers or “informal” caregivers. Individuals with dementia normally rely on multiple caregivers for necessary help and assistance.

The support family caregivers provide persons living with dementia (PLWD) is wide-ranging. Family caregivers assist with personal care, help manage other health conditions, communicate with the healthcare team, provide emotional support, and administer tasks of daily living, including both instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (e.g., transportation, shopping, cleaning) and activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g., bathing, dressing).

The help family caregivers provide benefits both the PLWD and the community. Thanks to family caregivers, PLWD can remain at home and contribute to and participate in their community longer, resulting in increased quality of life and better health outcomes. The help of family caregivers may also reduce the need for paid services.

What are the implications of dementia caregiving?

Caring for someone with dementia can be rewarding. However, the demands of dementia care can take a toll on a caregiver’s physical, mental, social, and financial well-being. Dementia caregivers often report higher levels of stress and depression and see a reduction in their social activities. The demands of caregiving can lead caregivers to neglect their own health and deprioritize seeking the care they need. Their care responsibilities can also have negative consequences on their employment and finances.

“Who cares for our loved ones when we have to go to work? Day centers average $85 to $125+ a day out of pocket. My most recent bill for three days a week, with a 20% discount and a $500 grant was $707 for one month. We are on a fixed income.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

- There are more than 11 million dementia caregivers in the US.1

- 2/3 of all dementia caregivers are women.1

- In 2010, family caregivers provided 78% of all care to people with dementia.2

- In 2022, family members and friends provided $339.5 billion in unpaid care.1

- Total payments in 2023 for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) are estimated at $345 billion, NOT including the value of informal caregiving.1

- Dementia caregivers are more likely than caregivers of other older people to assist with ADLs.3

- 59% of caregivers report high or very high levels of emotional stress associated with caregiving.1

- Dementia caregivers indicate a greater decrease in their social networks than other caregivers.4

- In a 2015 survey, 57% of caregivers reported being late to work an 18% cut back their work hours.3

- Dementia caregivers reported spending an estimated $8,978 on out-of-pocket costs related to caregiving in 2021.5

Examples from State Dementia Strategic Plans

This section provides an overview of the variety of dementia caregiving strategies individual states have selected to pursue as part of their jurisdictional strategic dementia plans. The strategies contained here are taken from previously published plans and have been synthesized to illustrate different kinds of public health approaches.

STRENGTHEN PARTNERSHIPS AND POLICIES

OUTCOME: Increase Community Partnerships

“We need resources from reputable sources leading us to support groups, caregiver education, and financial aid. A one-time $500 grant for respite care will not cover one week of a day center much less a month if the spouse needs to continue to work.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

- Identify and partner with nonprofit organizations dedicated to assisting those living with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders and their families, to offer free services such as transportation, household chores, companionship, and respite.

- Identify priority populations and invite their trusted community members and cultural organizations to the table early in the planning process. Actively involve them in all stages of the work, from selecting priorities, to finding additional partners, to implementing initiatives, etc.

- Help establish Dementia Friendly communities, health systems, businesses, faith communities, etc., using the Dementia Friendly America sector toolkits to support caregivers.

- Establish a permanent dementia-caregiver respite grant program.

- Facilitate connections and collaborations between health systems and community-based organizations that can enhance care and support for people with ADRD and their care partners.

- Encourage the business community to implement worksite wellness programs and dementia-friendly activities that encompass education and training for employees, including those who are caregivers.

- Encourage employers to expand their paid and unpaid leave options for caregiving for family members with dementia.

- Educate employers about the issues facing caregivers and encourage them to establish workplace policies such as flextime, telecommuting, referral services, on-site support programs, and counseling through Employee Assistance Programs.

- Encourage workplaces across sectors, including state government agencies to include assessing caregiver duties as part of annual employee surveys.

Dementia Friendly America is a national network of communities, organizations and individuals fostering the ability of people living with dementia to remain, age, and thrive in the community.

Learn more at: https://www.dfamerica.org

“I feel it’s essential, necessary, and very important: “nothing about us without us” is a slogan used to communicate the idea that no policy should be decided by any representative without the full and direct participation of the members of the group affected by this policy. We should be part of the conversation and the process of all efforts. I believe our insight and lived experience with our condition daily provide realistic input to understand the services needed for us, you have to see it through our lens…. When our voices and our choices are missing from committees, advisory panels, public policy and recommendations for bills, conferences, program initiatives and other efforts, the decisions made don’t always necessarily fit our immediate needs. When we are given these opportunities, we must not just be a necessary presence, but active participants to help facilitate changes that are very necessary to our well-being”

ANDREA R., person living with cognitive impairment

OUTCOME: Increase policy action and implementation

“In-home supportive service (IHSS), paid by Medicaid insurance, is an excellent resource. It helps provide personal care to this population and in turn, provides relief and may reduce emotional stressors to the families giving care and the person living with cognitive impairment. The providers can be family members, which can provide financial relief

to the person or family.”ANDREA R., person living with cognitive impairment

- Expand the Medicaid Home and Community Based Services Waiver Program.

- Expand availability and access of dementia-capable Medicaid and other state-level administered services.

- Educate policymakers about ADRD, the role of family caregivers, the impact of caregiving on their health, and recommend policy actions that can support family caregivers and protect their health and well-being.

- Expand Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provisions to include coverage for adult care.

- Preserve, restore, and increase established home- and community- based programs that effectively serve people with dementia and support their caregivers, including adult day services, in-home supportive services and Programs for All—Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE).

- Partner with the state legislature to advocate and advance policies that relieve the financial burden of care for families. Consider caregiver stipends, tax credits, reimbursements for respite care, and other grants that can be used to fund care performed at home and in the community.

- Develop emergency preparedness and response plans with resources and recommendations specific to people with dementia and their family caregivers that address the special needs of people with dementia and their family caregivers.

MEASURE, EVALUATE AND UTILIZE DATA

OUTCOME: Increase data availability, quality, and utilization

- Secure funding for and implement the Caregiver Module of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey at least every other year. Publicly disseminate key findings from the BRFSS for use in the development of programs and services.

- Gather and combine data from electronic medical records and different public health surveillance systems, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), Vital Records, and the Alzheimer’s Disease Registry, to track incidence of ADRD and its impact on caregiver health across the state.

- Work with service providers to create a coordinated and systematic way of collecting ADRD data in Medicaid and Medicare programs.

- Lead the development of a population based state dementia registry; and explore ways to collect, track, and use caregiver information to improve caregiver-supportive programming and services across the state.

OUTCOME: Increase data-informed decision making and action

- Use public health surveillance data and visualization in community education and outreach campaigns and when advocating for funding and support from legislators.

- Create interactive maps, overlying data from the BRFSS and other public health surveillance systems, with the location and type of supportive services and programs in the community. Use this data to inform program planning, prioritization, and allocation of resources.

BUILD A DIVERSE AND SKILLED WORKFORCE

OUTCOME: Reduce stigma and bias about cognitive decline

“We need education of the public, the first responders, physicians, courts, and even memory care centers. This is certainly a public health crisis.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

- Educate healthcare providers on the importance of having open and honest conversations regarding prognosis in severe dementia and how to assist families in making compassionate choices.

- Encourage the use of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant, web-based health-tracking tools that facilitate communication between informal caregivers and healthcare providers.

- Increase awareness among primary care clinicians and care partners of potentially avoidable causes of ED visits, hospital admissions, and readmissions for people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Emphasize the importance of partnership and communication between clinician and care partners.

OUTCOME: Increase knowledge and skills of current and future workforce

“We are ‘diagnosed and adios,’ leaving us with no real resources or support. We might get the number of the Alzheimer’s association, but we think in the fronto-temporal dementia (FTD) community how does that apply to us? We have to search ‘Dr. Google’ to even find out what FTD is…A person-centered care for all those with dementia is missing.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

- Endorse a set of evidence-based standards of care for dementia to promote high-quality health care.

- Incorporate mandatory training modules and continuing education on ADRD for medical school students, licensed doctors, and licensed nurses of all disciplines.

- Develop or collect and deliver dementia-specific, evidence-based training for various professions. Offer a certification and/or continuing education (CE) credits as incentives to participate in the training.

- Support certification, licensure, and degree programs that encourage working with older adults and people living with ADRD and their family caregivers.

- Promote caregivers and care partners as members of the medical team and integrate this component into medical training.

- Increase awareness of the need to involve caregivers in every step of care planning and goal setting for the person with cognitive impairment and dementia.

- Encourage hospitals to implement care models that include family caregiving in discharge planning and specific discharge instructions to the family.

- Increase awareness and advocate for inclusion of advance directives and end-of-life planning, including state-specific laws governing such practices, in routine care for all older adults, with particular emphasis on individuals with dementia and their caregivers.

- Provide education and guidance to care providers, care managers, and advocates on the Medicare benefit that reimburses for an annual cognitive exam. Also promote the use of Medicare coding to reimburse physicians and allied health professionals for family conferences and care consultation to educate family caregivers, guide future care decisions, and enhance the quality of medical care and support services.

- Collaborate with local Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP), medical and professional associations to develop educational curriculum for healthcare providers on how to include family caregivers in the care team, meet their health-related needs, etc.

- Work with your state’s certification program for Community Health Workers to develop a dementia-and caregiving-specific training curriculum or certification.

- Recruit and train dementia-care navigators to participate in the care of individuals with dementia and their family caregivers, ensuring that the patient receives appropriate care in the least restrictive setting throughout the progression of the disease.

“We need specialized case managers providing in-home support services to assist in navigating through available supported services. This is a very huge issue in our community.”

ANDREA R., person living with cognitive impairment

- Incorporate educational materials and information about support and services for patients and family caregivers into digital libraries that physicians and other care providers can store and forward on electronic medical records.

- Develop and implement electronic referral systems to community-based resources for caregivers and patients diagnosed with dementia.

- Work with healthcare organizations to systematically identify caregivers within the electronic medical record (EMR) as part of routine dementia care. Use it to regularly include the caregivers in care conversations and also to screen their needs for support services.

- Provide public recognition of professional roles in public health, healthcare, and social services that work with people living with dementia and their caregivers.

ENGAGE AND EDUCATE THE PUBLIC

OUTCOME: Increase public knowledge about brain health, risk factors for dementia, and benefits of early detection and diagnosis

“A person diagnosed with dementia needs palliative care from diagnosis… Educating on the difference between palliative care and hospice care is vital in getting referred to a palliative care team to address quality of life issues.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

- Empower family caregivers to register for, participate in, and complete training in established educational programs offered by reliable public and not-for-profit organizations with expertise in ADRD. Increase participation in educational programs among care-givers through culturally and linguistically appropriate offerings.

- Promote and increase access to legal education for individuals living with ADRD and their caregivers. Encourage caregivers to learn about the financial and legal impact of ADRD and the importance of obtaining professional advice.

- Educate caregivers on the importance of advance care planning and encourage them to actively discuss palliative care, hospice, end-of-life issues, and right-to-die with the healthcare team.

- Collaborate with healthcare providers to educate patients diagnosed with dementia and their families on next steps, care planning, and other supportive services for both the person with dementia and the family caregivers.

- Implement a culturally and linguistically appropriate public health awareness campaign to promote the importance of identifying and assessing the health and well-being of caregivers. Messaging

should use available public health data on caregiving and include calls to action. - Promote positive and diverse images of people living with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers to combat stigma and improve societal acceptance and integration.

- Integrate messaging about caregiving as a health risk factor into existing public health campaigns related to prevention and chronic disease. Include language that promotes self-care and frequent breaks for caregivers.

OUTCOME: Increase public knowledge and use of services for people living with dementia and their caregivers

“Consider investing in more resources such as national public health hotline numbers. Connect the individual with resources in their state. Ensure resources and services are up to date regularly.”

ANDREA R., person living with cognitive impairment

- Create, publicize, and maintain a state-wide inventory of all public and private organizations that offer evidence-based programs, supports, and services for family caregivers.

- Collaborate with members of the state dementia coalition to jointly develop and/or promote a centralized, state-wide database of ADRD-related resources, information, and referrals for both care –

givers and persons living with dementia.

For caregivers, the portal can be accessible via telephone or web, offer multimedia educational materials, programs, training, and resources on a variety of topics related to caregiving (e.g., self-care and caregiver well-being, addressing behavioral issues, supports available in the community, etc.) - Disseminate information regarding culturally competent support services for caregivers, including respite, care coordination, and case management services, in a manner, time, and location

that meets caregiver and care-recipient needs and preferences. - Work with private and public partners to produce and disseminate multilingual information regarding availability and eligibility criteria for all dementia-related, state-supported, and private services and

programs for family dementia caregivers. - Promote existing training offered in the state, locate and disseminate an evidence-based program available nationally, or create a state-endorsed training program for family caregivers. Programs may include financial support or incentives for universities and schools to offer low-cost or free family caregiver training options. Incentivize family caregivers to participate by offering tax incentives and/or certificates upon successful completion of the program.

- Create and disseminate an inventory of face-to-face and web-based support groups for family caregivers available in the state. Encourage the establishment of additional caregiver support groups in areas currently lacking such groups.

- Partner with community organizations and aging service providers in rural and geographically remote areas to promote programs and disseminate web and paper-based tools and materials.

- Promote Best Practice Caregiving (BPC) to coalition partners and encourage implementation of evidence-based programs via grant awards and make them a requirement in RFPs for state

funding and grant opportunities.Once BPC develops its consumer oriented portal, promote it to caregivers as a way for them to locate programs available in their community that can meet their needs.

Best Practice Caregiving is a searchable, online database of proven dementia programs for family caregivers. It is an invaluable tool for funders, public health, healthcare and community organizations to find, disseminate, and implement high-quality programs for caregivers.

Implementation Examples from States

Stories from the Field

This section provides examples of activities different states and counties have undertaken to support dementia caregivers as part of their strategic dementia plan. While the initiatives listed below were not always led or initiated by public health departments, they provide ideas of partnerships and opportunities for public health action.

STRENGTHEN PARTNERSHIPS AND POLICIES

ARIZONA

“A Multi-Pronged Approach to Supporting Caregivers”In consultation with multiple private and public partners across the state, the Arizona Department of Health Services developed a 3-part strategy to support dementia caregivers throughout the continuum of dementia care: linkages to care, a universal helpline for caregivers, and a training program for public health professionals.

Linkages to care was modeled after the HIV Rapid Start Adherence initiative which was focused on providing coordinated and streamlined support, and connection to services and programs to individuals. The caregiver support program was to have a single point of contact for the individual caregiver, who would help them navigate the system of community services and support and would ensure care was provided in a timely manner.

The universal helpline for caregivers is available to assist caregivers in navigating and coordinating different kinds of services. Also called the Caregiver Resource Line, the helpline can be accessed by phone at 1-888-737-7494 and on the web at: http://www.azcaregiver.org. In addition to the Caregiver Resource Line, the 2-1-1 Arizona Information and Referral services program can also help caregivers locate and connect with community services.

The training program is a curriculum-based Train-The-Trainer program for public health professionals to educate and train dementia caregivers. Titled “Finding Meaning and Hope (FM+H)”, the program is a series of structured weekly conversations led by a trained facilitator and intended to build self-management skills among dementia family caregivers. FM+H also includes other wrap-around resources for caregivers, such as mindfulness training, creative art, and continued group support. Results from the initial pilot indicated improved physical and behavioral health self-management, self-care behaviors, and reduced stress in caregivers.

LOUISIANA

“Empowering Employers to Support Caregivers”The Louisiana Department of Health partnered with the Office for Aging and Adult Services and the state Alzheimer’s Association chapter to develop a workplace training titled “Caregivers in the Workplace”. The training aims to educate supervisors about the challenges and impacts of caregiving on employee well-being and help them identify and support employees who are caregivers. The training module includes background information about the signs and symptoms of ADRD and the role of the caregiver. It also teaches how to recognize signs of employee stress, offers recommendations for how to approach and respond to employees dealing with caregiving stress, as well as emphasizing the importance of connecting employees with supportive resources and education for balancing caregiving and work.

The training was embedded into a central platform state employees use for payroll, benefits, and all required training. To encourage participation, Continuing Education Units (CEUs) were offered for Social Workers.

To learn more about Louisiana’s Caregivers in the Workplace training, watch this video.

“We must turn to others who are in the FTD community for help, the stress can be unbearable…Those with young onset dementia have to go on social security disability when they lose their job and benefits long before their full retirement age. They must wait two full years to have Medicare. Meanwhile, the spouse has to continue to work, they can’t afford to stay home, and they need the insurance coverage.”

SHARON H., caregiver to husband with dementia

MISSISSIPPI

“Building Coalitions and Leveraging Partnerships for Collective Impact”Upon receiving the BOLD Core Capacity program award, the Mississippi State Department of Health began its work by conducting a statewide scan of organizations and groups active in the space of dementia. They quickly identified and joined an existing Steering Committee for the State of Mississippi Strategic Plan for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (“Alzheimer’s State Plan”) that was already leading dementia-related work across the state. Two years into the partnership, the department of health regularly attends quarterly group meetings, is part of key committees, and participates in an annual summit where partners meet, progress is reviewed, and shared goals are set for the following year by the group.

The department of health brings to the partnership experience and access to different sources of public health data. Under their leadership, data from the BRFSS Cognitive Decline and Caregiving modules are now shared and utilized by coalition partners in decision making and health promotion.

To grow the caregiver support infrastructure, the Mississippi State Department of Health is partnering closely with The Memory Impairment and Neuro-degenerative Dementia (MIND) Center at the University of Mississippi Medical Center to increase access to chronic disease self-management programs for dementia caregivers. It is also developing an interactive map of community resources that can help identify gaps

in caregiver services and inform state program planning and outreach.Finally, the department is also applying an equity lens to its Alzheimer’s State Plan with assistance from a designated group of Health Equity Ambassadors, identifying and addressing social determinants of health most closely related to ADRD. The ambassadors are identifying and implementing a minimum of two activities annually within their assigned Goal Group to address social determinants of health for ADRD in Mississippi.

Invest in culturally trained outreach workers specialized in working with this population. Collaborate with other agencies that are already doing the work, pulling your resources together.”

ANDREA R., person living with cognitive impairment

NEW YORK

“Supporting Caregivers in the Workplace”In 2021, New York became the first state in the nation to begin collecting data on employed caregivers, both in the public and private sector. Through data and findings from previously published national studies, the New York State Office for the Aging (NYSOFA) recognized that many employees are juggling their roles as caregivers along with work responsibilities. Business leaders also understood that the impact on their employees who are caregivers can be felt through missed time, disruptions in the workday, losses in productivity, or worse—the permanent loss of trained, hardworking employees who are an integral part of a business.

The NYSOFA first launched the Working Caregiver Survey in 2021. The survey is still open and can be accessed at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/WorkingCaregiverSurvey. The state partnered with a wide range of state, county, and private employers, as well as state officials and associations to disseminate the survey as broadly as possible. The purpose of the survey is to further enhance the state’s understanding of who working caregivers are, who they are caring for, the amount of time per week they are providing care, what services are lacking to support them, and what opportunities exist to increase utilization of caregivers supports and services. Employers can also use survey findings to learn about the experiences and needs of their caregiver employees, and how they can help them.

In addition to the survey, NYSOFA collaborated with the NYS Department of Labor to develop “Caregivers in the Workplace”, a resource guide for HR departments, business leaders and supervisors to support their working caregivers and connect them with existing community support services. NYSOFA also developed a 10-minute training video that employers can offer to their employees. The video helps caregivers self-identify and connects them with tools, resources, and support.

In addition to the survey, NYSOFA collaborated with the NYS Department of Labor to develop “Caregivers in the Workplace”, a resource guide for HR departments, business leaders and supervisors to support their working caregivers and connect them with existing community support services. NYSOFA also developed a 10-minute training video that employers can offer to their employees. The video helps caregivers self-identify and connects them with tools, resources, and support.As part of its broader, state-wide effort to support caregivers, NYSOFA partnered with Trualta to offer Trualta’s evidence-based caregiver training and support platform free-of-charge to any caregiver in NYS. The training can be accessed through the New York Caregiving Portal, and is designed to support caregivers through enhanced skills training, education, and connection to existing community support services.

Finally, NYSOFA also partnered with ARCHANGELS to provide access to their Caregiver Intensity Index (CII) tool. The CII helps caregivers understand where they are in their caregiver journey, identify their needs, and connect them to resources and supports to reduce stress.

To view these and other resources New York State has in place to support caregivers in the workplace, visit Help for Working Caregivers.

MEASURE, EVALUATE AND UTILIZE DATA

CALIFORNIA

“A State Scorecard to Monitor Progress and Drive Change”In January 2021, California published its Master Plan on Aging, outlining 5 strategic goals that will guide the state’s aging priorities and work over the next decade. As part of the Master Plan on Aging, California also developed the state’s Data Dashboard for Aging which allows it to monitor and ensure progress towards implementation of the plan. The dashboard provides data visualizations of the different strategies under each goal, along with links to specific topics and information at the county level. To construct the data indicators, numerous public data sources relevant to each strategy were leveraged, including data on income, transportation, demographics, disease prevalence, health spending, community services, etc. All data is continuously updated, and new indicators continue to be incorporated into the state scorecard.

By incorporating an evaluation plan from the beginning of the planning process, public health and its partners can use the data to inform policy, programs, and services, and make continuous improvements. Data and visualizations from the dashboard can also be leveraged in public health communication campaigns and to make the case for action to different partners and decision makers. The Dashboard was a collaboration between the California Department on Aging, the California Department of Health, and the West Health Institute.

To learn more about the different data sources used to build the dashboard, visit California’s Data Dashboard on Aging: About the Data.

NORTH DAKOTA

“Using Data to Align Dementia with other Chronic Disease Efforts and to Inform Programming”North Dakota Department of Health (NDDH) was able to utilize funding from its Comprehensive Cancer Control grants to implement the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Cognitive Decline and Caregiver modules. The data gathered in these BRFSS modules allowed the public health department to identify specific health needs and challenges faced by dementia caregivers. It also helped establish caregivers as a priority population for other chronic disease programs across the state, such as oral health, diabetes, and hypertension.

The BRFSS data also informed the NDDH’s partnerships with the aging service providers in its chronic disease management efforts. The data was used to adapt programming to better meet the needs of dementia caregivers, offering more virtual and asynchronous program delivery options, among others.

Finally, the BRFSS Subjective Cognitive Decline and Caregiving data was used to develop and select key strategies for North Dakota’s State Dementia Plan.

To learn more about North Dakota’s work, watch From Data to Action: Using the BRFSS to Advance the Public Health Agenda of Dementia Caregiving.

TEXAS

“Understanding the needs of unpaid caregivers” In 2021, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) Alzheimer’s Disease Program (ADP) and the Chronic Disease Epidemiology Branch collaborated with the volunteer-based Texas Alzheimer’s Disease Partnership (Partnership) to create the 2021 Texas Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Caregiver Survey. The purpose of the survey was to learn more about the experiences of unpaid caregivers of people with ADRD. Questions addressed satisfaction with services and support available in the community, satisfaction with information and resources received from government and healthcare entities, as well as demographic data.

In 2021, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) Alzheimer’s Disease Program (ADP) and the Chronic Disease Epidemiology Branch collaborated with the volunteer-based Texas Alzheimer’s Disease Partnership (Partnership) to create the 2021 Texas Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Caregiver Survey. The purpose of the survey was to learn more about the experiences of unpaid caregivers of people with ADRD. Questions addressed satisfaction with services and support available in the community, satisfaction with information and resources received from government and healthcare entities, as well as demographic data.To disseminate the survey as broadly as possible, DSHS used the networks of partner organizations and a snowball sampling method to reach potential respondents. Partnership members and key collaborators forwarded the email with the survey link to unpaid caregivers and others who might know unpaid caregivers. The survey link was also posted to the DSHS LinkedIn and Twitter social media pages. The survey results confirmed that caregiving can have a profound impact on unpaid caregivers’ health, work, and finances. This information contributes to a better understanding of what kinds of services and supports are needed

and available to support unpaid caregivers across the state. Additional data is needed to better understand the impact of caregiving on diverse populations in Texas of different racial, ethnic, linguistic, geographic, and socioeconomic backgrounds.DSHS will use this information to inform state plan priority areas and suggested activities that emphasize the needs of family caregivers and the importance of research on caregiving issues. To view more details about survey development, methodology, and results, please see the full report “2021 Texas Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Caregivers Survey Report”.

WISCONSIN

“Leveraging Different Sources of Data” The Wisconsin Department of Health Services is in the process of completing a data project analyzing retrospective claims data from the Medicaid long term care program with a focus on reducing preventable hospitalizations for people with dementia. Examining claims data from dually-eligible individuals over four years (2016–2019), results pointed to the largest number of preventable hospitalizations being among individuals living at home with family caregivers.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services is in the process of completing a data project analyzing retrospective claims data from the Medicaid long term care program with a focus on reducing preventable hospitalizations for people with dementia. Examining claims data from dually-eligible individuals over four years (2016–2019), results pointed to the largest number of preventable hospitalizations being among individuals living at home with family caregivers.The second phase of the project involved a survey of the family caregivers of the Medicaid program participants. Many of the Managed Care Organizations that administer the program in Wisconsin were supportive partners in the project and carried out a short survey with the caregivers of current enrollees. The survey asked about any support that was accessed prior to and after enrollment. An offer of additional educational material was also made to caregivers as a part of the survey. Results of the survey demonstrated that approximately half of all family caregivers received no support from either paid or unpaid sources prior to enrollment in the Medicaid program.

The final phase of the current project will be to evaluate whether caregivers receiving support had any effect on the occurrence of preventable hospitalizations.

BUILD A DIVERSE AND SKILLED WORKFORCE

MINNESOTA

“Expanding the Care Team” Community Health Workers (CHWs) are community members who work to provide basic health education, coordination, and support in their communities. As essential members of the care team and trusted members in their communities, CHWs facilitate and coordinate care between healthcare systems and community settings, and connect patients with relevant, culturally appropriate community-based services. In Minnesota, there is strong support for CHWs to expand their knowledge and skills in providing culturally responsive education on dementia risk reduction and early detection and supporting people living with dementia and their care partners.

Community Health Workers (CHWs) are community members who work to provide basic health education, coordination, and support in their communities. As essential members of the care team and trusted members in their communities, CHWs facilitate and coordinate care between healthcare systems and community settings, and connect patients with relevant, culturally appropriate community-based services. In Minnesota, there is strong support for CHWs to expand their knowledge and skills in providing culturally responsive education on dementia risk reduction and early detection and supporting people living with dementia and their care partners.The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) has worked with community partners to provide ongoing dementia education for CHWs. In collaboration with Volunteers of America (VOA) Culturally Responsive Caregiver Support and Dementia Services team, the MDH Oral Health Unit developed a Train-The-Trainer curriculum for CHWs to educate dementia caregivers about the importance of maintaining good oral health in older adults experiencing dementia. Building off the success of this partnership, the new MDH Healthy Brain Initiative partnered with VOA to build additional dementia risk reduction content into their virtual education platform for adults through a new monthly segment called “Know Your Risks: Brain Health”.

Given the ability of CHWs to provide culturally responsive preventative care, education, and referrals, MDH worked with VOA and other CHW partner organizations to further understand ongoing education needs related to dementia. In response to recommendations from Minnesota’s 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Working Group Report to the MN Legislature highlighting the importance of culturally responsive strategies and workforce training, MDH is currently working with the Minnesota Community Health Worker Alliance (MNCHWA) to develop a dementia-focused training for CHWs covering culturally responsive risk reduction, early detection, disease management, and caregiver support with input from CHWs. This training will be disseminated in 2023 and evaluated to assess its reach and impact.

GEORGIA

“Training First Responders” BOLD using Systemic Education, Evidence, and Networks (B-SEEN) is a collaboration between the Georgia’s Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias (GARD) Advisory Council and Georgia Department of Public Health, in charge of planning and implementation state-wide dementia efforts as part of Georgia’s BOLD grant.

BOLD using Systemic Education, Evidence, and Networks (B-SEEN) is a collaboration between the Georgia’s Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias (GARD) Advisory Council and Georgia Department of Public Health, in charge of planning and implementation state-wide dementia efforts as part of Georgia’s BOLD grant.Early in the project, the team identified the need for first responder training on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. In collaboration with the GARD Workforce Development group, B-SEEN has since developed training to educate first responders and public health professionals on general dementia education and experiences of those living with dementia and their caregivers. In the short term, the goal of the training will be to provide a Continuing Education Unit (CEU) learning opportunity for first responders. In the long run, the training will assist first responders in providing person-centered responses in situations involving people living with dementia and avoiding unnecessary harm or injury.

The training modules went live in early 2023 and were integrated into TRAIN, a centralized learning management system with free training opportunities for public health and emergency preparedness professionals in Georgia. Including the training in a shared, multi-agency learning platform will facilitate access to the training and inclusion in the regular public health staff training program.

In addition to the training, the B-SEEN team has also partnered with Second Wind Dreams, a nonprofit dedicated to developing educational programs and training to change perceptions about aging and dementia. In May 2022, B-SEEN provided Second Wind’s Virtual Dementia Tour (VDT) Certified Trainer training to an initial group of employees. In May of 2023, newly certified trainers facilitated a largescale VDT event for a group of first responders in their area. A second event is planned for late August 2023.

ENGAGE AND EDUCATE THE PUBLIC

MICHIGAN

“Expanding the Caregivers’ Support System” In recent years, the state of Michigan engaged a broad, state-wide coalition with more than 65 organizations including healthcare systems, universities, state agencies, service providers and many others to implement a joint healthy aging action plan. Collective efforts sought to enable older adults to age in place by obtaining the designation of an age-friendly state, prioritizing dementia among people with HIV and investing in caregiver support.

In recent years, the state of Michigan engaged a broad, state-wide coalition with more than 65 organizations including healthcare systems, universities, state agencies, service providers and many others to implement a joint healthy aging action plan. Collective efforts sought to enable older adults to age in place by obtaining the designation of an age-friendly state, prioritizing dementia among people with HIV and investing in caregiver support.Specifically, to expand caregiver support state-wide, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Aging and Adult Services Agency and its partners expanded an existing 77-hour training for professional caregivers (Building Training… Building QualityTM) and developed a pilot training for high school students. For family caregivers, the agency also secured a grant from the Michigan Health Endowment Fund to embed caregiver assessment of care they are providing and referrals to support through selected area agencies on aging.

NEW MEXICO

“Aligning Agency Efforts to Reach More Caregivers”In New Mexico, the state Department of Health teamed up with the New Mexico Aging and Long-Term Services Department to encourage caregivers to take part in two different courses, Savvy Caregiver and Chronic Disease Self-Management (CDSM). Savvy Caregiver is offered by the Aging and Long-Term Services Department and is designed to help caregivers address daily challenges of dementia care. The New Mexico Department of Health offers a CDSM course that helps people living with chronic disease manage their health. The two agencies partnered to co-market their courses and each one encouraged its participants to enroll in the other course.

Caregivers are likely to have chronic diseases, and are more likely to neglect their own care because of responsibilities associated with caregiving. By participating in both courses, caregivers are equipped with tools to better take care of their own health while also caring better for the person living with dementia.

OHIO

“Selecting Interventions that Work”The Summit County Public Health Department (SCPH), OH used its Alzheimer’s Disease Programs Initiative (ADPI) grant from the Administration for Community Living to identify and deliver an evidence-based intervention (EBI) to support caregivers of people with dementia. The goal of the grant was to select and deliver an EBI that would help caregivers manage behavioral issues and reduce their stress, improve the quality of life for both caregiver and the person living with dementia, and positively impact disease progression and functional decline.

To select the best program for their community, the SCPH conducted initial research to better understand the caregiver support needs in their population. Based on the findings, the team was able to identify key intervention components that would meet the education and training needs of the caregivers it serves. The SCPH then worked with developers and agencies that had implemented different interventions to evaluate their effectiveness in improving quality of life for the caregiver and their care recipient, as well as their impact on functioning, safety, and health care utilization. The SCPH also identified the support and services that would be needed in the local community as part of the intervention. After a thorough review of a number of available evidence-based programs, the team selected the BRI Care Consultation (BRICC).

Since its implementation, the BRICC has shown promising results. 90% of caregivers who have been referred or recommended to BRICC decide to enroll. Preliminary outcomes show improvements in caregiver well-being, geriatric depression, and quality of life for the person living with dementia. Goals related to BRICC were also part of Ohio State 2020–2022 Strategic Action Plan on Aging. SCPH is currently pending funding notification from the Ohio Department of Aging to develop an “Alzheimer’s and Related Dementia’s Statewide Resource Program”. If funded, this Ohio state-led project will enable SCPH, along with other ADPI recipients, to build a support platform for caregivers across Ohio.

WASHINGTON

“A state Road Map for Caregivers” In addition to the strategic state dementia plan, which is intended for public health agencies and their partner organizations, states can also develop a state plan for use by individuals living with dementia and their caregivers.

In addition to the strategic state dementia plan, which is intended for public health agencies and their partner organizations, states can also develop a state plan for use by individuals living with dementia and their caregivers.The Washington State Department of Health has developed one such plan, Dementia Road Map: A Guide for Family and Care Partners. This guide is designed to offer direction and tips to help caregivers navigate the difficult journey of caring for someone with dementia and orient them to supportive services and programs available in the community.

WISCONSIN

“Dementia Care Specialist Program” The mission of the Dementia Care Specialist (DCS) Program in Wisconsin is to support people with dementia and their caregivers in order to ensure the highest quality of life possible while living at home. To achieve this, the DCS program consists of three pillars.

The mission of the Dementia Care Specialist (DCS) Program in Wisconsin is to support people with dementia and their caregivers in order to ensure the highest quality of life possible while living at home. To achieve this, the DCS program consists of three pillars.The first pillar provides a dementia-capable, county-based agency for anyone to access at no cost when looking for information or assistance related to long-term care or Older American Act services. Staff also provide memory screening upon request or recognition of need. Results of the screen may include a referral to a physician for evaluation, and/or education on a variety of topics, from maintaining brain health to resources for support. The program educates and empowers individuals and their caregivers to discuss brain health with their healthcare providers. Program services are provided to anyone requesting them and a prior diagnosis is not required.

The second pillar of the program is to be a catalyst for developing dementia friendly communities. Dementia friendly communities supported by DCS include a volunteer dementia coalition as well as dementia friendly customer service training to help businesses provide better service to people living with dementia and their families. Training is available to pharmacies, banks, government offices and other entities people access to live independently in the community. Memory Cafes are another important component of dementia friendly communities. The Cafes are designed to be welcoming, supportive community spaces where people living with dementia and their care partners can socialize and connect with others going through similar experiences.

The third pillar focuses on providing direct support to individuals and families. Two interventions must be offered as part of the DCS program: one evidence-based focused on supporting family caregivers, and a second one, evidence-based or evidence-informed, designed for either the caregiver or person living with dementia. In addition, dementia care specialists also provide one-on-one meetings to assist families reaching for help in times of crisis.

Watch this recording to hear more about the Dementia Care Specialists in Wisconsin.

WISCONSIN

“Developing an Online Training for Family Caregivers” The Wisconsin Office on Aging, which is housed in the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health’s Bureau of Aging and Disability Resources, was awarded a grant from the Administration for Community Living (ACL) in 2014, and then again in 2019.

The Wisconsin Office on Aging, which is housed in the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health’s Bureau of Aging and Disability Resources, was awarded a grant from the Administration for Community Living (ACL) in 2014, and then again in 2019.In partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, a training was developed to teach family caregivers how to handle the behavioral symptoms of dementia in an effective way, first in English, and then in Spanish in the subsequent grant. The online course covers the fundamentals of dementia and provides family caregivers with caregiving skills to keep in mind when providing care for someone whose behavior has changed due to dementia. The training includes video vignettes that demonstrate how to handle a variety of behavioral symptoms, such as anger and aggressiveness, expressed by the person living with dementia. It also provides tips for how to take care of oneself as a family caregiver, and how to support family members who are caring for a dementia patient.

The subsequent Spanish language version included cultural adaptations, featuring Spanish-speaking actors and translation.

Both English and Spanish versions can be found on the Wisconsin Department of Health Services website here: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/dementia/families.htm.

Links to Individual State Dementia Strategic Plans

Appendix

The below table contains links to most-recently published state dementia strategic plans. This list of strategic plans is current as of June 2023. Some plans might have since been updated and users should confirm that they are viewing the most up-to-date version of each plan. As new plans become available, they are uploaded and can be viewed on CDC’s State and Jurisdictions Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Plans page.

References

1Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2023;19(4). DOI 10.1002/alz.13016

2Friedman EM, Shih RA, Langa KM, Hurd MD. US Prevalence And Predictors Of Informal Caregiving For Dementia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015 Oct;34(10):1637-41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510. Erratum in: Health Aff (Millwood). 2015 Nov;34(11):2006. PMID: 26438738; PMCID: PMC4872631

3National Alliance for Caregiving in Partnership with the Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia Caregiving in the U.S. Bethesda, MD. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Dementia Caregiving-in-the-US_February-2017.pdf

4Liu C, Fabius CD, Howard VJ, Haley WE, Roth DL. Change in Social Engagement among Incident Caregivers and Controls: Findings from the Caregiving Transitions Study. J Aging Health 2021; 33(1-2):114-24

5AARP. 2021 Caregiving Out-Of-Pocket Costs Study. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00473.001. Available at www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/ltc/2021/family caregivers-cost-survey-2021.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00473.001.pd